Amputees frequently experience a sense of detachment from their prosthetic devices, particularly bionic hands, which can hinder their functionality and user satisfaction. A research team led by Marshall Trout at the University of Utah has made promising progress toward bridging this gap by partnering artificial intelligence (AI) with advanced sensor technology to create a more responsive and intuitive prosthetic hand.

The core challenge in prosthetic hand control lies in reliably recognizing the user's intended movements and translating these intentions into natural actions. Conventional bionic hands can respond to electrical signals from muscles but often require intense concentration and lack the subtle reflexive control inherent to biological limbs. These limitations contribute to difficulties in performing delicate tasks, such as gripping a cup without crushing or dropping it, leading to user frustration and abandonment of the device.

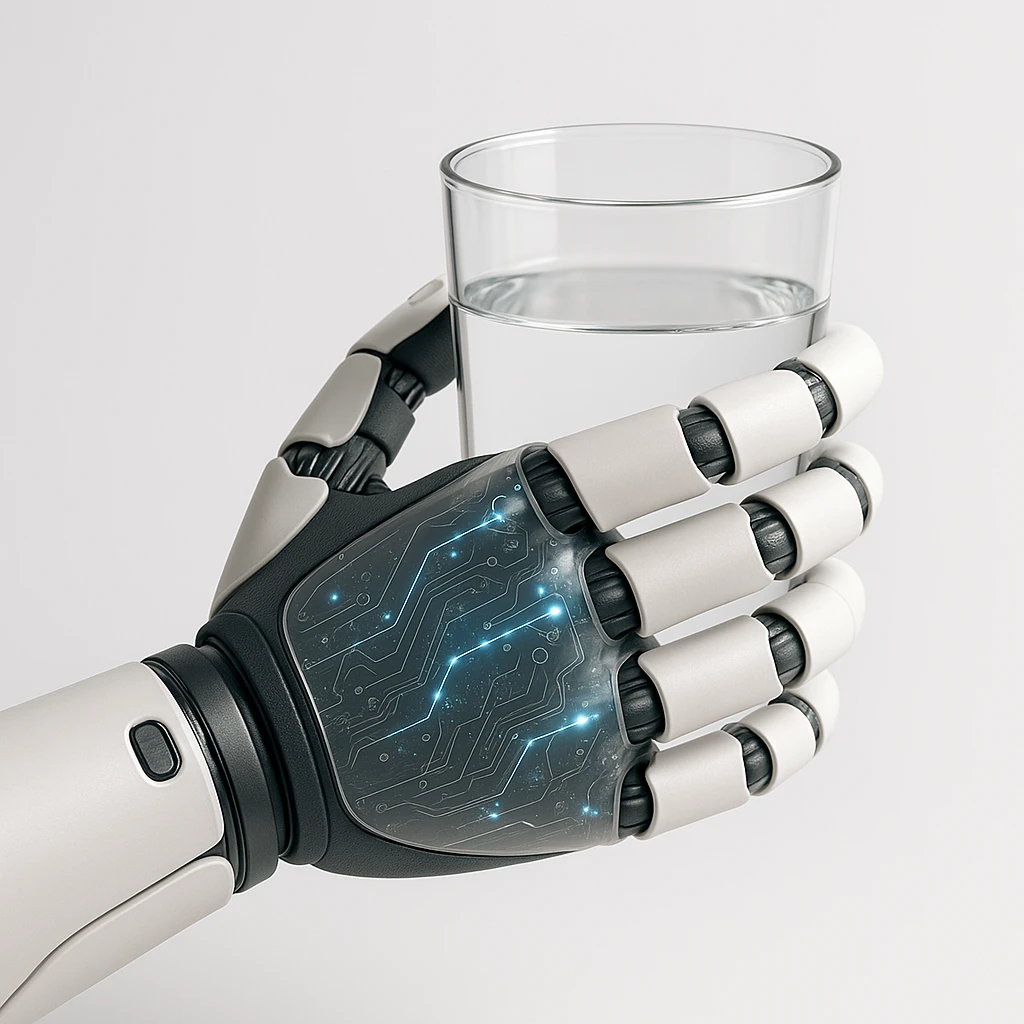

To tackle this, researchers designed a bionic hand system that integrates AI algorithms with proximity and pressure sensors embedded in the prosthetic. The AI analyzes minute muscle twitches—such as a slight flexing of the hand muscle—to detect when the user aims to grasp an object. At the same time, the system gauges environmental factors like object distance, shape, and firmness through the sensors, enabling it to assist in modulating grip strength and finger positioning.

In a study involving four individuals with arm amputations, participants tested the enhanced prosthetic by simulating drinking from a cup. With the AI-assisted shared control, they were able to grasp the cup securely and perform the motion reliably. Without this assistance, the participants consistently either crushed the cup or failed to maintain a grip, emphasizing the significance of the shared control mechanism.

John Downey, an assistant professor at the University of Chicago who was not involved in the study, highlighted the importance of these achievements by noting that managing grasp force remains a critical hurdle in current prosthetics research. He explained that natural hand movements involve not only conscious commands but also reflexive actions controlled subconsciously by neural circuits in the brainstem and spinal cord. The AI approach emulates these reflexive loops, sharing control between human intention and machine response to create a fluid and effective interaction.

Jacob George, director of the Utah NeuroRobotics Lab, underscored the necessity of this cooperative control framework by observing that prosthetics with capabilities exceeding those of a biological hand often feel alien to users, who resist relinquishing control to fully robotic motions. The smart bionic hand developed in this project preserves users’ sense of agency by blending their inputs with automated adjustments derived from sensor data and AI interpretation.

Trout likened the system to the natural handling of everyday objects. He described how, with a biological hand, once a person initiates an action such as reaching for a coffee cup, much of the fine motor adjustment proceeds subconsciously, requiring minimal deliberate focus. The AI-enabled prosthetic aims to recreate this effortless interaction, reducing mental strain and enhancing usability.

Despite advancements, experts acknowledge that even the most sophisticated bionic hands cannot yet fully replicate the dynamic range and precision of natural limbs across all activities, such as transitioning from delicate tasks like threading a needle to exerting force when lifting a child. However, as prosthetic technology continues to evolve, maintaining human control alongside AI assistance will remain paramount to user acceptance and device effectiveness.

This research, published in the journal Nature Communications, signals a pivotal step toward transforming prosthetic limbs from mere tools into integrated extensions of users' bodies, capable of restoring a more natural and intuitive experience for amputees.