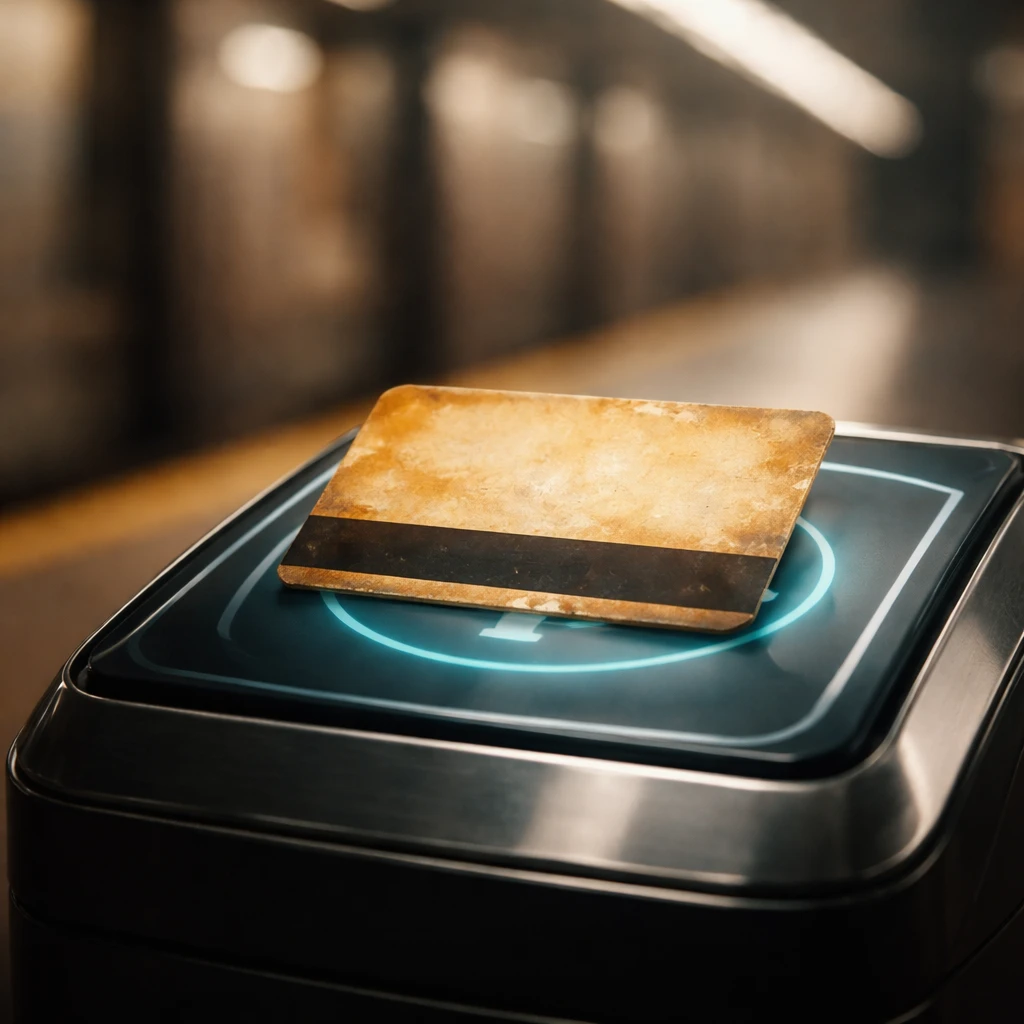

For more than three decades, the MetroCard has been an essential part of navigating New York City's sprawling transit system. Introduced in 1994 by the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA), this blue and yellow magnetic-stripe card revolutionized fare payment for millions of commuters and tourists taking to the city's buses and subways. However, as of January 1, the MTA will cease selling MetroCards, ushering in a new phase that encourages the adoption of OMNY (One Metro New York), a contactless payment method featuring tap-to-pay functionality via smartphones, smartwatches, credit cards, or dedicated OMNY cards.

Though existing MetroCards will remain operational for a limited time, the MTA has yet to announce a final acceptance date, signaling the impending retirement of a transit icon that has long been woven into the rhythm of the city. This transition represents not just a technological upgrade but also a significant cultural shift, affecting millions of daily riders and the urban landscape itself.

From Tokens to Magnetics: The Evolution of Fare Payment

Before the advent of the MetroCard, New Yorkers primarily used subway tokens, which debuted in 1953 and were distinctive in their design—roughly dime-sized with an engraved "NYC" featuring a hollowed-out "Y." While tokens were simple to carry and use, requiring passengers to deposit them into turnstiles or fareboxes, they posed challenges for the MTA when adjusting fares, necessitating cumbersome changes to coin acceptance mechanisms.

The idea to modernize fare collection gained momentum in the early 1980s when Richard Ravitch, then MTA commissioner, proposed replacing tokens with a stored-value magnetic stripe card system. His vision aligned with trends in other cosmopolitan cities seeking to streamline transit payments. Though initially considered a tool to reduce fare evasion, the MetroCard’s introduction saw fare evasion persist, albeit in altered forms such as the use of improperly modified cards known as "swipers" or hacking activities that compromised card security.

Beyond combating fare evasion, the MetroCard offered riders more versatile fare options, including discounted rates for seniors, people with disabilities, and students, as well as the popular unlimited-ride monthly passes. A landmark benefit over tokens was the ability to transfer between buses and subways on a single fare, a feature that eased travel across the city’s transit network.

MetroCards as Cultural Artifacts and Collectibles

The MetroCard did not merely function as a payment device; it became a collectible emblem of New York City life. The MTA released an inaugural limited edition card in 1994, the same year the MetroCard launched, and since then, approximately 400 specially designed commemorative cards have appeared. These editions often celebrated notable events such as Grand Central Terminal’s centennial or marked local sports milestones like the first Yankees-Mets game in 1997, the "Subway Series." Advertising has also played a significant role, representing a vital revenue source for the MTA.

Certain editions have taken on symbolic significance. For example, the David Bowie MetroCards, created to celebrate a museum exhibit at the Broadway-Lafayette station in partnership with Spotify and the Brooklyn Museum, drew long queues of eager buyers. Other notable cards include those commemorating the 50th birthday of rapper Notorious B.I.G. and collaboration cards with fashion brands such as Supreme.

For collectors like Mike Glenwick, who began accumulating MetroCards at age six, the cards serve as tangible memories, connecting users to the city’s history and moments. Glenwick’s collection exceeds 100 cards, many highlighting major New York sports achievements, underscoring the cultural integration of the MetroCard.

An Artistic Medium and Symbol of New York Spirit

The MetroCard has inspired artistic reinterpretation as well. Artist Thomas McKean has transformed discarded MetroCards into works of art ranging from mosaics to sculptures, capturing the vivid aesthetics and tactile qualities of the card. What began as a spontaneous creative experiment during a subway ride grew into a dedicated artistic pursuit, with McKean’s creations exhibited in galleries, featured on magazine covers, and sold through commissions, including clients outside New York who share an affection for the city’s iconography.

McKean conserves a substantial reserve of unused cards and recycles every viable piece, reflecting both a respect for the material and a commitment to preserving the card’s legacy through art. His work will soon be displayed in an exhibition at the New York Transit Museum's Grand Central gallery, cementing the MetroCard’s status not just as a functional item but as a medium of cultural expression.

The Shift to OMNY and Its Implications

The MTA’s new fare payment system, OMNY, enables riders to simply tap a contactless device against turnstiles or bus readers, streamlining the process and offering payment via mobile wallets or traditional credit and debit cards. For those without electronic payment means, the MTA provides OMNY cards purchasable with cash for $1 at vending machines and select retailers.

However, the transition has raised concerns about access equity, particularly for unbanked populations who may lack credit or debit cards. While the MTA has not commented publicly on the timeline for discontinuing cash acceptance, the possibility echoes trends among retailers gradually moving away from cash transactions. This raises important questions about inclusivity within the city’s public transportation system.

From the MTA’s perspective, OMNY promises operational efficiencies, with expected annual savings of $20 million resulting from lower costs in card production, maintenance, and cash handling. Furthermore, the tap-based system simplifies fare calculation for riders, particularly with policies such as free unlimited rides after the 12th trip in a week.

Despite these advantages, long-time MetroCard users express mixed feelings. Glenwick, for instance, acknowledges the practical benefits of OMNY but feels a sentimental attachment to the MetroCard, describing its impending phaseout as the loss of a “childhood” artifact and preferring to hold onto the card for as long as possible.

Conclusion

The retirement of the MetroCard marks the end of a significant chapter in New York City’s transit history. Alongside technological progression toward contactless payments, it reflects broader changes in urban mobility, cultural practices, and economic considerations. As the city embraces OMNY, the MetroCard remains a symbol of decades of commuting stories, cultural moments, and artistic inspiration, encapsulating a unique aspect of New York City identity that will endure even as the card itself disappears from turnstiles.