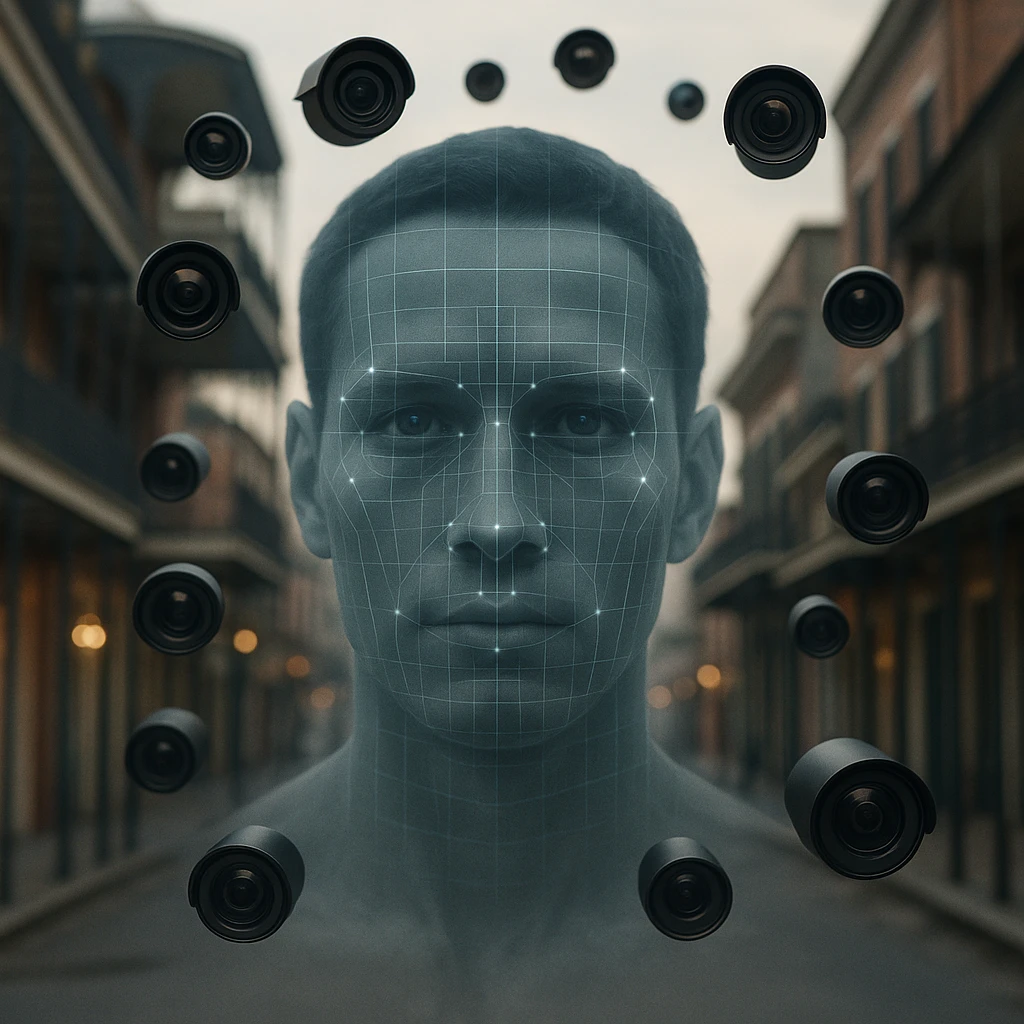

New Orleans, widely known for its vibrant culture and bustling nightlife, now finds itself at the forefront of a new surveillance paradigm as it hosts the nation’s first live facial recognition network managed by a private nonprofit organization rather than the police department. This innovative approach began taking shape as a grassroots response to public safety concerns in the years following Hurricane Katrina, when the city struggled with limited police resources.

Project NOLA, launched in 2009 by Bryan Lagarde—a former police officer—has built an extensive surveillance infrastructure, incorporating feeds from over 5,000 privately owned cameras positioned throughout the city. These cameras operate largely on private properties, with volunteers paying annual fees to participate in the network. The nonprofit functions as a centralized hub that aggregates the video streams and employs live facial recognition technology to identify persons of interest in real-time.

Lagarde describes the cameras as a "force multiplier" for law enforcement resources. In 2022, the project enhanced its system by adding live facial recognition software to process and analyze the voluminous video data more efficiently. Approximately 200 of the most advanced cameras are equipped with this capability, continuously scanning faces in crowded areas such as the French Quarter. The software searches against a database of roughly 250 individuals categorized on "hot lists," which include persons suspected of serious criminal involvement, such as gang activity or firearms violations.

When a face is matched with someone on these lists, an automated alert is generated and conveyed to Project NOLA staff with accompanying contextual information. Lagarde explains that these notifications may prompt sharing information with law enforcement agencies when the data substantiates ongoing investigations. He emphasizes that the nonprofit seeks to document patterns, such as the frequency and nature of alleged criminal conduct, rather than responding to isolated suspicions.

Despite the operational success of live facial recognition in identifying suspects and preventing crime according to project leadership, a revelation of Project NOLA’s practices by the Washington Post in May 2025 sparked controversy. Local authorities and civil rights advocates expressed concern over the legal framework governing such extensive surveillance conducted by a non-governmental entity.

Sarah Whittington, Advocacy Director of the ACLU of Louisiana, asserted that while New Orleans law permits some use of facial recognition by local agencies, it does not authorize live real-time facial recognition operated by third-party organizations. Consequently, collaboration between Project NOLA and the New Orleans Police Department (NOPD) was suspended by Police Superintendent Anne Kirkpatrick, who stated that they would not authorize real-time alerts to officers until compliance with local ordinances was ensured.

Kirkpatrick reiterated her support for live facial recognition technology as a valuable tool, clarifying that her action did not reflect opposition but was aimed at ensuring legal adherence. She noted the challenges of addressing privacy protection when the technology is controlled by private entities rather than public agencies.

The regulatory ambiguity surrounding live facial recognition is further complicated at the federal level. Although the Supreme Court has ruled that continuous tracking using certain technologies requires probable cause and a warrant, no specific federal laws regulate the real-time use of facial recognition by law enforcement. Legal scholars caution that engagement of private organizations in surveillance may serve as a mechanism bypassing constitutional protections.

Project NOLA asserts that it operates with strict safeguards to protect individual privacy. Every facial recognition request tied to law enforcement investigations is documented with case numbers to confirm legitimacy. Plans are underway to increase transparency by publishing data on facial recognition requests and participating agencies through a public website.

Interestingly, the nonprofit does not exclusively answer to law enforcement; it also provides unsolicited tips to NOPD about persons of interest detected by the system but continues independent monitoring according to Lagarde. He argues that Project NOLA offers greater accountability compared to city or federal systems, given that camera deployment depends on private community consent and can be discontinued by property owners if desired.

Meanwhile, city officials remain undecided about formalizing regulations for live facial recognition technology. A proposed city council ordinance aimed at structuring police partnerships with third-party facial recognition providers and imposing reporting obligations did not advance. Discussions also considered authorizing NOPD to develop an in-house live facial recognition system, but concerns about potential federal or state access—especially amid heightened immigration enforcement—have stalled progress.

Among the public and local business owners, opinions vary. Visitors to Bourbon Street often remain unaware that cameras overhead are actively identifying faces, with some expressing unease about privacy but recognizing the importance of accountable governance. Conversely, some business owners, such as Tim Blake of the Three Legged Dog bar, endorse the system, reporting increased safety and behavioral improvements from patrons influenced by visible surveillance.

This debate in New Orleans highlights broader questions about who should wield control over advanced surveillance technologies, striking a balance between public safety and individual rights. It serves as an early example of the complexities inherent in deploying live facial recognition within a framework of private operation intersecting with public law enforcement objectives.