Authorities in South Carolina have confirmed an additional 124 measles cases since last Friday, intensifying an outbreak predominantly located in the northwestern area of the state. This surge follows the recent holiday period and has pushed the total in South Carolina to 434 cases as of Tuesday, with Spartanburg County identified as the focal point of the outbreak.

The rapid expansion over the past month has positioned this outbreak as one of the nation’s most severe. Hundreds of children have faced quarantine requirements due to exposure at schools, some being subjected to isolation on multiple occasions. Moreover, a confirmed individual with measles has been linked to potential exposures at the South Carolina State Museum in Columbia. Current projections suggest that this case count could soon approach the magnitude of a previous outbreak in Texas last year, which recorded 762 cases and tragically resulted in two children’s deaths. Experts caution that the Texas figures may have underrepresented the true scale of the spread.

Concurrently, health agencies monitoring the region straddling the Arizona-Utah border, particularly the towns known as Hildale, Utah, and Colorado City, Arizona — collectively referred to as Short Creek — report sustained growth in measles infections. Since August, 418 individuals in this area have been diagnosed with measles. Specifically, Arizona’s Mohave County has documented 217 cases, including nine new ones added on Tuesday, while Utah health officials have confirmed a total of 201 cases, marking an increase by two on the same day.

Authorities in both states express concern regarding potential underreporting of actual cases. Nicole Witt from the Arizona Department of Health Services noted a temporary reduction in case numbers before an uptick following the holiday season. She expressed cautious optimism about ending the outbreak but indicated that new cases continue to emerge in small numbers weekly.

Measles is an airborne viral illness characterized by symptoms such as high fever, cough, runny nose, red watery eyes, and a distinctive rash. It initially infects the respiratory system and then disseminates throughout the body. Though most children recover, the disease carries the risk of serious complications including pneumonia, vision loss, inflammation of the brain, and death.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) report that last year was the worst year nationally for measles incidence since 1991, confirming 2,144 cases across 44 states. The fatalities recorded numbered three, all in individuals who were not vaccinated.

Measles spreads easily via airborne droplets when an infected person breathes, sneezes, or coughs. Because of its contagiousness, it is classified as a disease that was considered eliminated in the United States since 2000; however, recent outbreaks challenge this status.

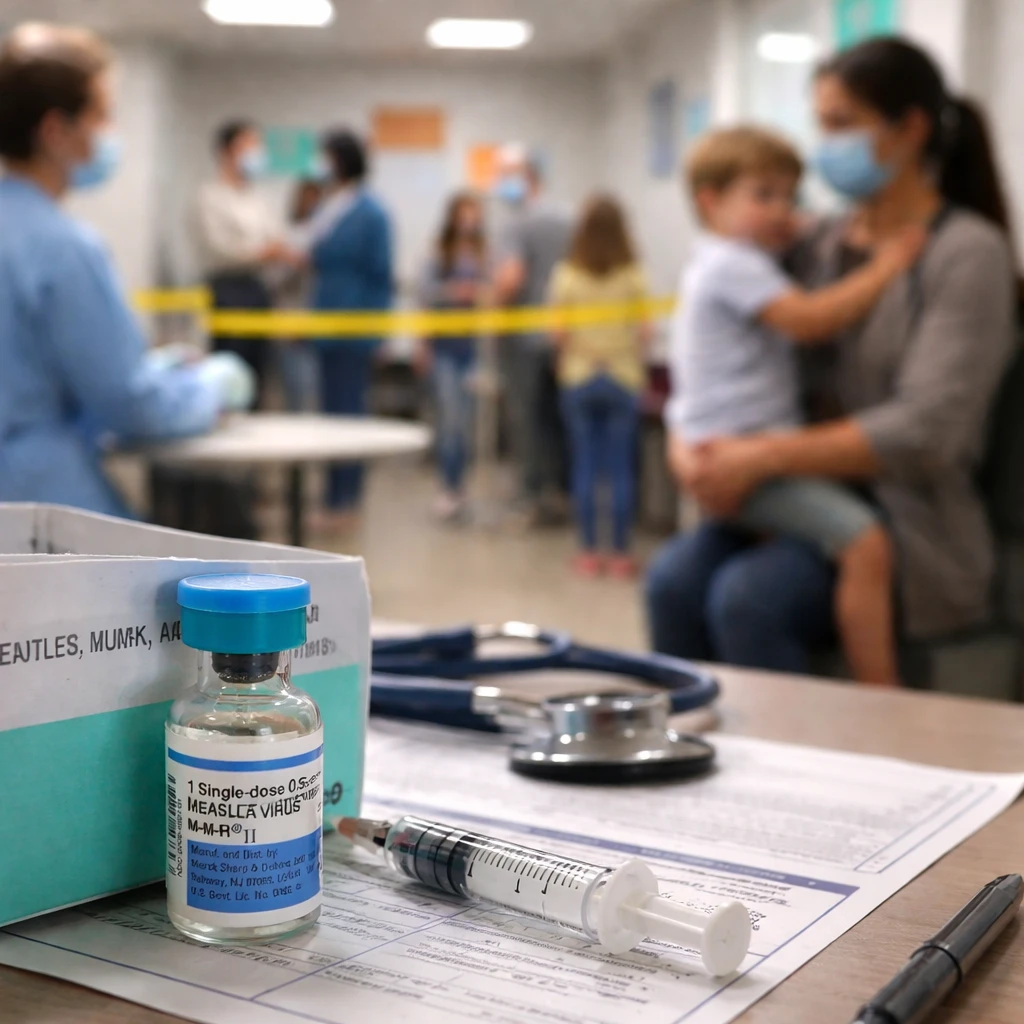

The primary defense against measles is the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine. It is recommended that children receive the first dose between 12 and 15 months of age and a second dose between four and six years old. When administered in two doses, the vaccine is approximately 97% effective and provides lifelong immunity.

Communities with vaccination levels exceeding 95% benefit from herd immunity, significantly reducing the disease’s capacity to spread. Yet nationwide, childhood vaccination rates have declined since the COVID-19 pandemic began, and an increasing number of parents are seeking exemptions on religious or personal grounds.

The CDC defines an outbreak as the occurrence of three or more related measles cases, highlighting the scale at which these current instances qualify.